Nick Hyatt, Director of Threat Intelligence, Blackpoint Cyber

May 30, 2024

4 Min Read

Source: kaarle dev via Alamy Stock Photo

COMMENTARY

In 2023, there were more than 23,000 vulnerabilities discovered and disclosed. While not all of them had associated exploits, it has become more and more common for there to be a proverbial race to the bottom to see who can be the first to release an exploit for a newly announced vulnerability. This is a dangerous precedent to set, as it directly enables adversaries to mount attacks on organizations that may not have had the time or the staffing to patch the vulnerability. Instead of racing to be the first to publish an exploit, the security community should take a stance of coordinated disclosure for all new exploits.

Coordinated Disclosure vs. Full Disclosure

In simple terms, coordinated disclosure is when a security researcher coordinates with a vendor to alert them of a discovered vulnerability and give them time to patch before making their research public. Full disclosure is when a security researcher releases their work to the wild without restriction as early as possible. Nondisclosure (which, as a policy, isn't relevant here) is the policy of not releasing vulnerability information publicly, or only sharing under nondisclosure agreement (NDA).

There are arguments for both sides.

For coordinated vulnerability disclosure, while there is no specific endorsed framework, Google's vulnerable disclosure policy is a commonly accepted baseline, and the company openly encourages use of its policy verbatim. In summary, Google adheres to the following:

Google will notify vendors of the vulnerability immediately.

90 days after notification, Google will publicly share the vulnerability.

The policy does allow for exceptions, listed on Google's website.

On the full disclosure side, the justification for immediate disclosure is that if vulnerabilities are not disclosed, then users have no recourse to request patches, and there is no incentive for a company to release said patch, thereby restricting the ability of users to make informed decisions about their environments. Additionally, if vulnerabilities are not disclosed, malicious actors that currently are exploiting the vulnerability can continue to do so with no repercussions.

There are no enforced standards for vulnerability disclosure, and therefore timing and communication rely purely on the ethics of the security researcher.

What Does This Mean for Us, As Defenders, When Dealing With Published Exploits?

I think it's clear that vulnerability disclosure is not going away and is a good thing. After all, consumers have a right to know about vulnerabilities in the devices and software in their environments.

As defenders, we have an obligation to protect our customers, and if we want to ethically research and disclose exploits for new vulnerabilities, we must adhere to a policy of coordinated disclosure. Hype, clout-chasing, and personal brand reputation are necessary evils today, especially in the competitive job market. For independent security researchers, getting visibility for their research is paramount — it can lead to job offers, teaching opportunities, and more. Being the "first" to release something is a major accomplishment.

To be clear, reputation isn't the only reason security researchers release exploits — we're all passionate about our work and sometimes just like watching computers do the neat things we tell them to do. From a corporate aspect, security companies have an ethical obligation to follow responsible disclosure — to do otherwise would be to enable attackers to assault the very customers we are trying to defend.

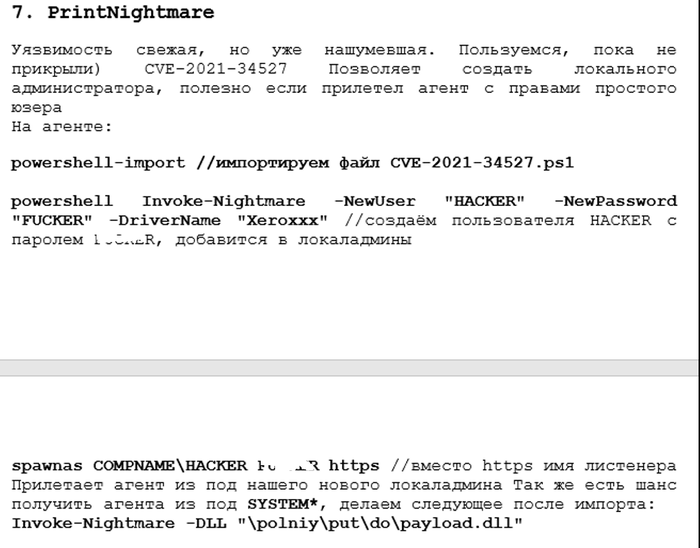

It's no secret that malicious actors monitor security researchers, to the extent that threat actors have integrated researcher work into their toolkits (see Conti's integration of PrintNightmare exploits):

This is not to say that researchers shouldn't publish their work, but, ethically, they should follow the principle of responsible disclosure, both for vulnerabilities and for exploits.

We recently saw this around the ScreenConnect vulnerability — several security vendors raced to publish exploits — some within two days of the public announcement of the vulnerability, as with this Horizon3 blog post. Two days is not nearly enough time for customers to patch critical vulnerabilities — there is a difference between awareness posts and full deep dives on vulnerabilities and exploitation. A race to be the first to release an exploit doesn't accomplish anything positive. There is certainly an argument that threat actors will engineer their own exploit, which is true — but let them take the time to do so. The security community does not need to make the attacker's job easier.

Exploits are intended to be researched in order to provide an understanding of all the potential angles that the vulnerability in question could be exploited in the wild.

The research for exploits, however, should be internally performed and controlled, but not publicly disclosed in a level of detail that benefits the threat actors looking to leverage the vulnerability, due to the frequency that publicly marketed research of exploits (Twitter, GitHub, etc.) via well-known researchers and research firms, are monitored by these same nefarious actors.

While the research is necessary, the speed and detail of disclosure of the exploit portion can do greater harm and defeat the efficacy of threat intelligence for defenders, especially considering the reality of patch management across organizations. Unfortunately, for this day age in the current threat landscape, exploit research that is made public, even with a patch, does greater harm than good.

8 months ago

36

8 months ago

36